Project overview

Problem

A local elementary librarian was looking for ways to introduce self-service maker activities in their elementary library that a) were safe for their wide-range of students and b) could increase engagement in classroom-related learning.

Method

This project was completed in four weeks. Service design methods were used, which employed a collaborative, iterative process that focused on human-centered approaches and design thinking:

- discovery (e.g., customer consultation and value proposition; empathizing through observation and creating an empathy map),

- interpretation (e.g., searching for meaning, framing opportunities),

- ideation (e.g., collaborative brainstorming, collaboratively creating service design blueprint),

- experimentation (e.g., designing props and resources, testing with students, focus group for feedback), and

- evolution (e.g., reflecting on process, iterating for improved service design, designing final user flow).

Impact

The improved service-design optimized safety by 68% for the 500+ students and teachers who used the self-service makerspace lab.

My role

I led consultations with the librarian and volunteers, which included facilitating human-centered approaches to optimize the makerspace service, observing needs, identifying opportunities, and designing options for self-directed activities with safe materials that the elementary students could easily use without adult assistance. Additionally, I collaborated with my own university students to develop instructional materials to be included in the space.

Process details

Discovery

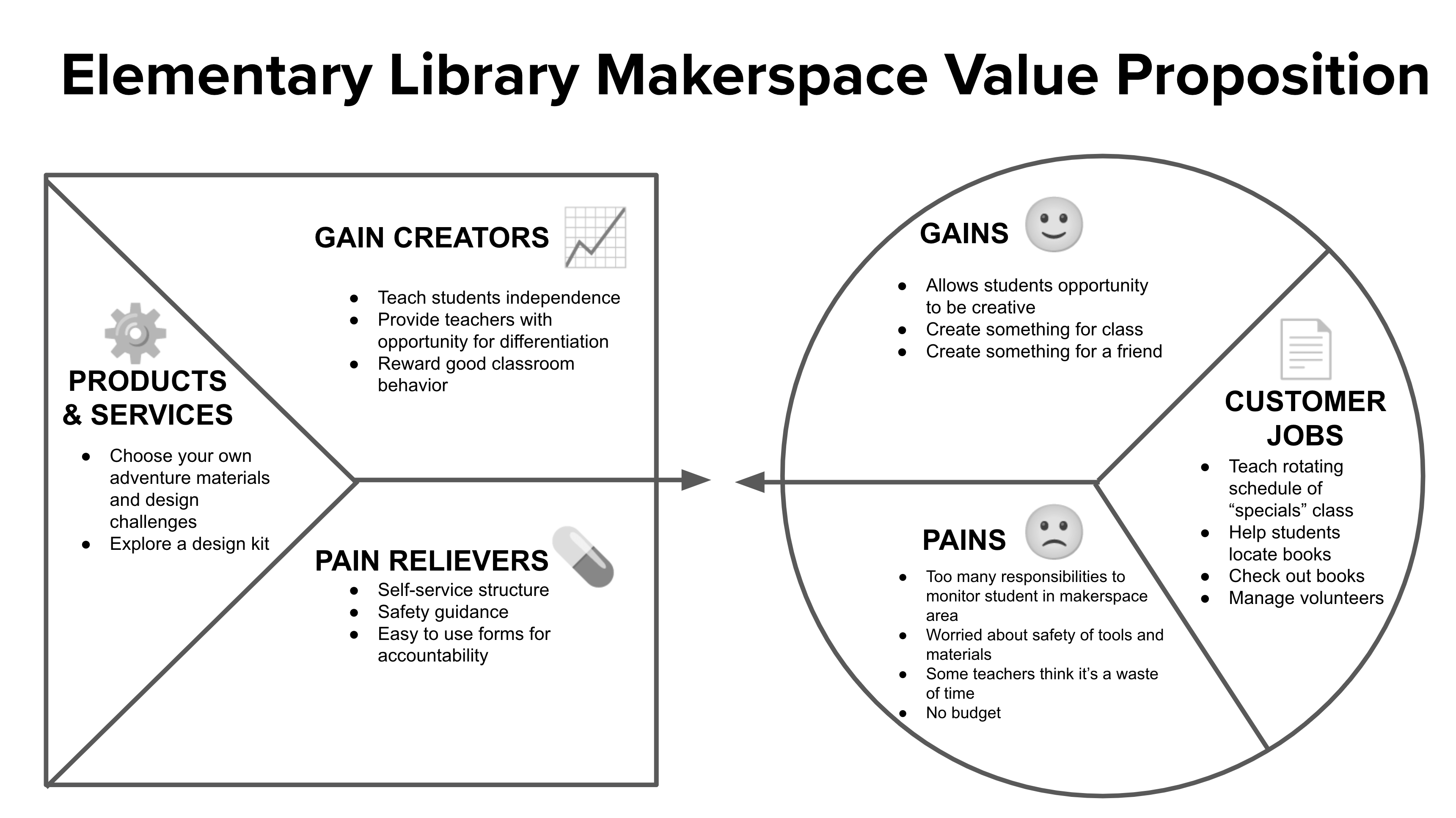

This project focused on 1) designing a space that was conducive for self-directed student activities and 2) designing activities that connected the making to reading and classroom concepts. The first step in the process was discovering user needs. I began with a kickoff meeting to understand the librarian’s potential pains, gains, and day-to-day jobs, which we collaboratively mapped on a value proposition canvas together (see Figure 2).

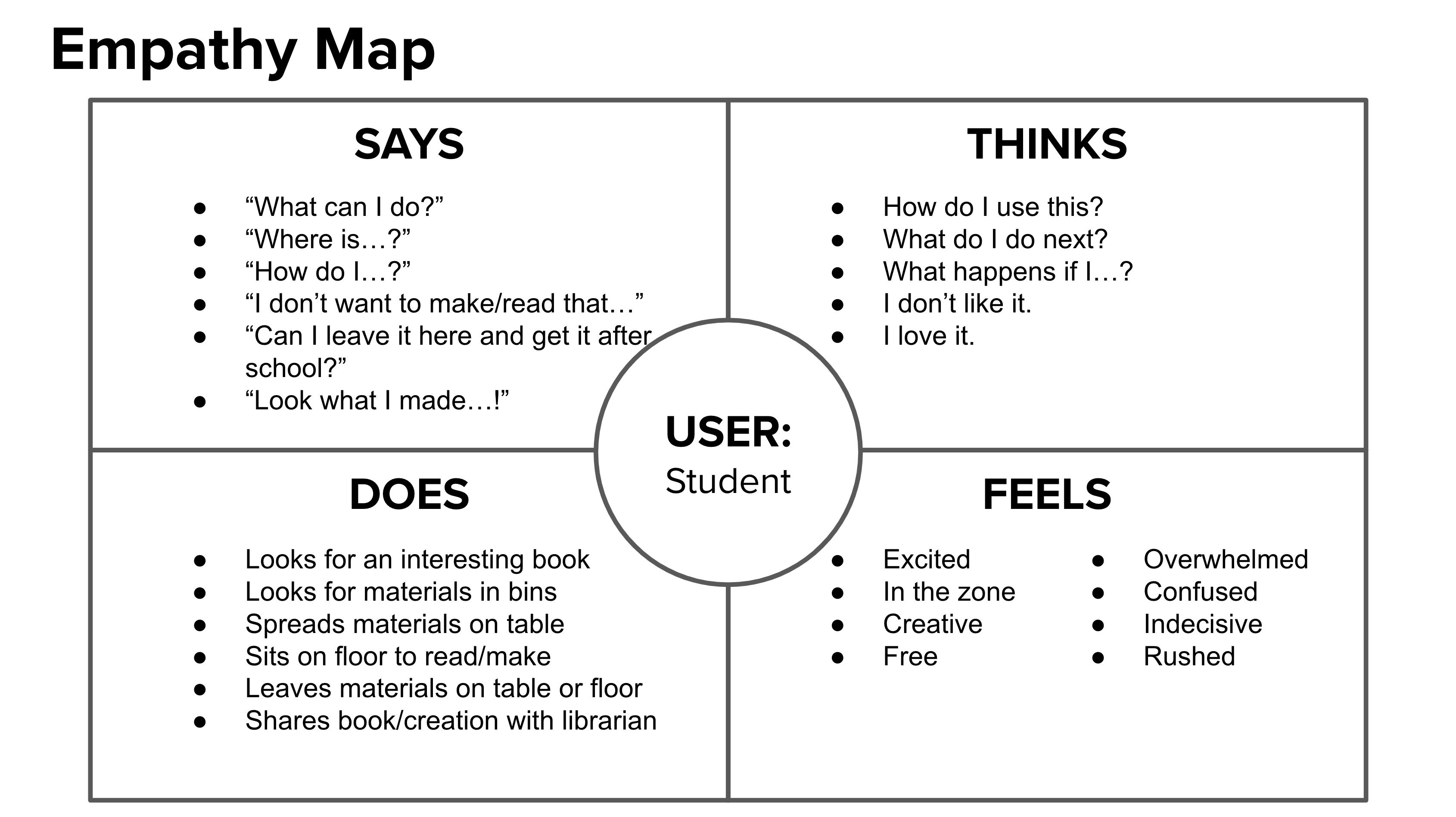

I then observed the needs of the librarian and the students in the context of the library space, which was used to create an empathy map to help the librarian further understand the needs for the space (see Figure 3). I spent one day observing in the library so I could see what a typical day was like for the librarian (e.g., teaching literacy lessons to classes on the “specials” schedule, helping students find books of interest, and managing volunteers who monitored book check-in and check-out). These observations aligned with the value proposition that we had collaboratively made beforehand.

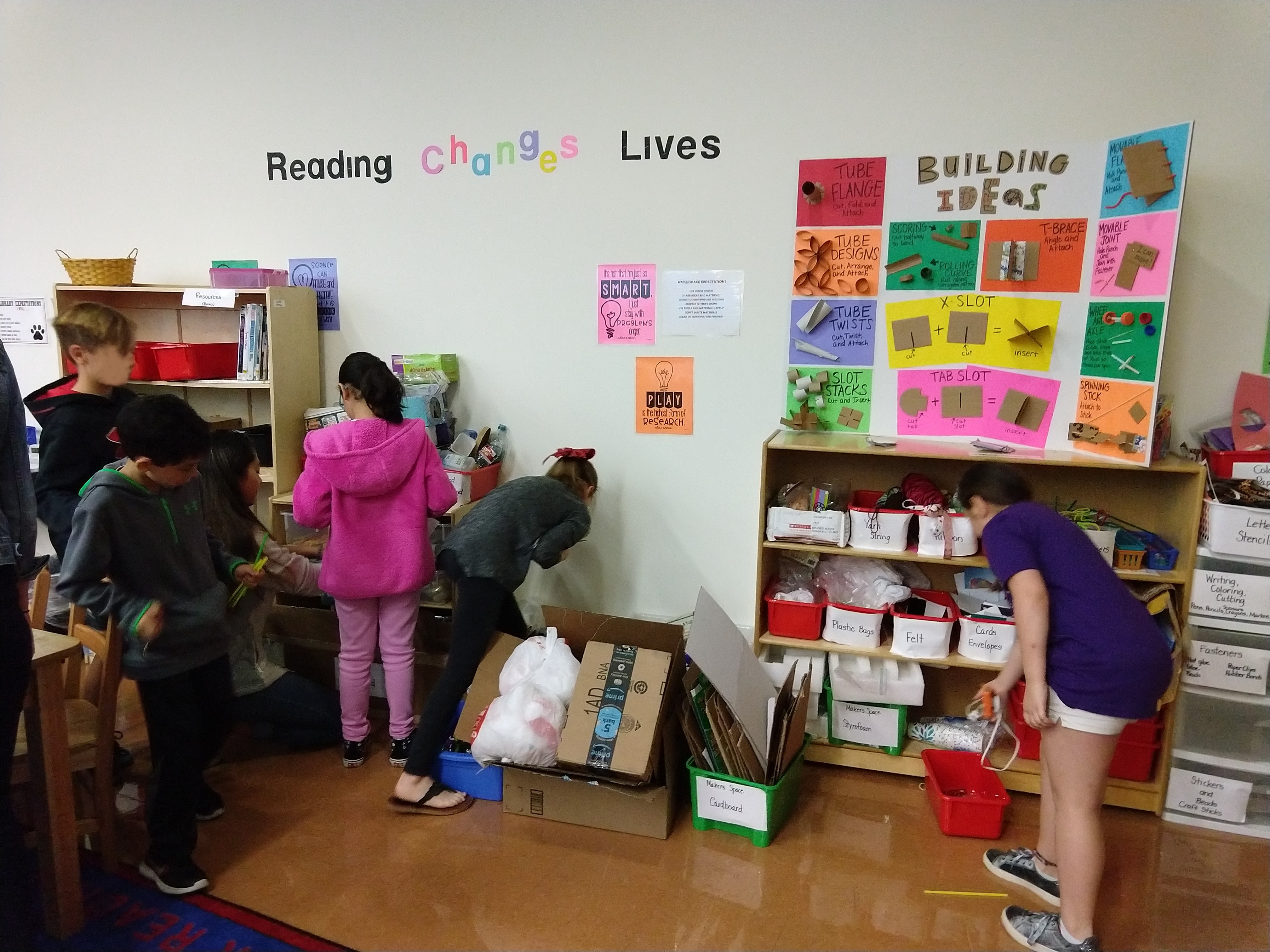

Additionally, I spent a day observing different groups of students as they engaged in various activities within the library (e.g., looking for interesting books on curated collection shelves, sitting in chairs and on the floor to read books and write book reports, working on assignments for class, and considering craft materials in the makeshift makerspace corner area but not using them).

Interpretation

During my interpretation of the observations, I noticed that 1) the librarian and the volunteers were consistently busy overseeing classes and individual student book needs and 2) a small corner in the library with various craft materials was not used much throughout the day. I posed the following How Might We question to help frame opportunities:

“How might we design a self-directed makerspace area in the library for elementary students so that they can safely make creations related to their reading or learning?”

Ideation

The ideation step involved debriefing with the librarian and volunteers to discuss observations and define opportunities to address needs on sticky notes. First, we discussed how students could use the space without adult supervision to find a balance between desirability, feasibility, and viability. When considering tools and materials, we focused heavily on safety. The librarian provided a list of items that had previously caused minor incidents requiring a band-aid or a quick visit to the nurse’s office, estimating about 25 such incidents over a semester. Because there was no budget, we discussed what materials the librarian already had access to, which included various kits (e.g., Legos, Snap Circuits, Little Bits) and craft materials (e.g., adhesives, recyclables, donated ribbon) they had been collecting in the back room. We also considered what types of examples could be created to visually demonstrate techniques (i.e., minimize the need for instructions).

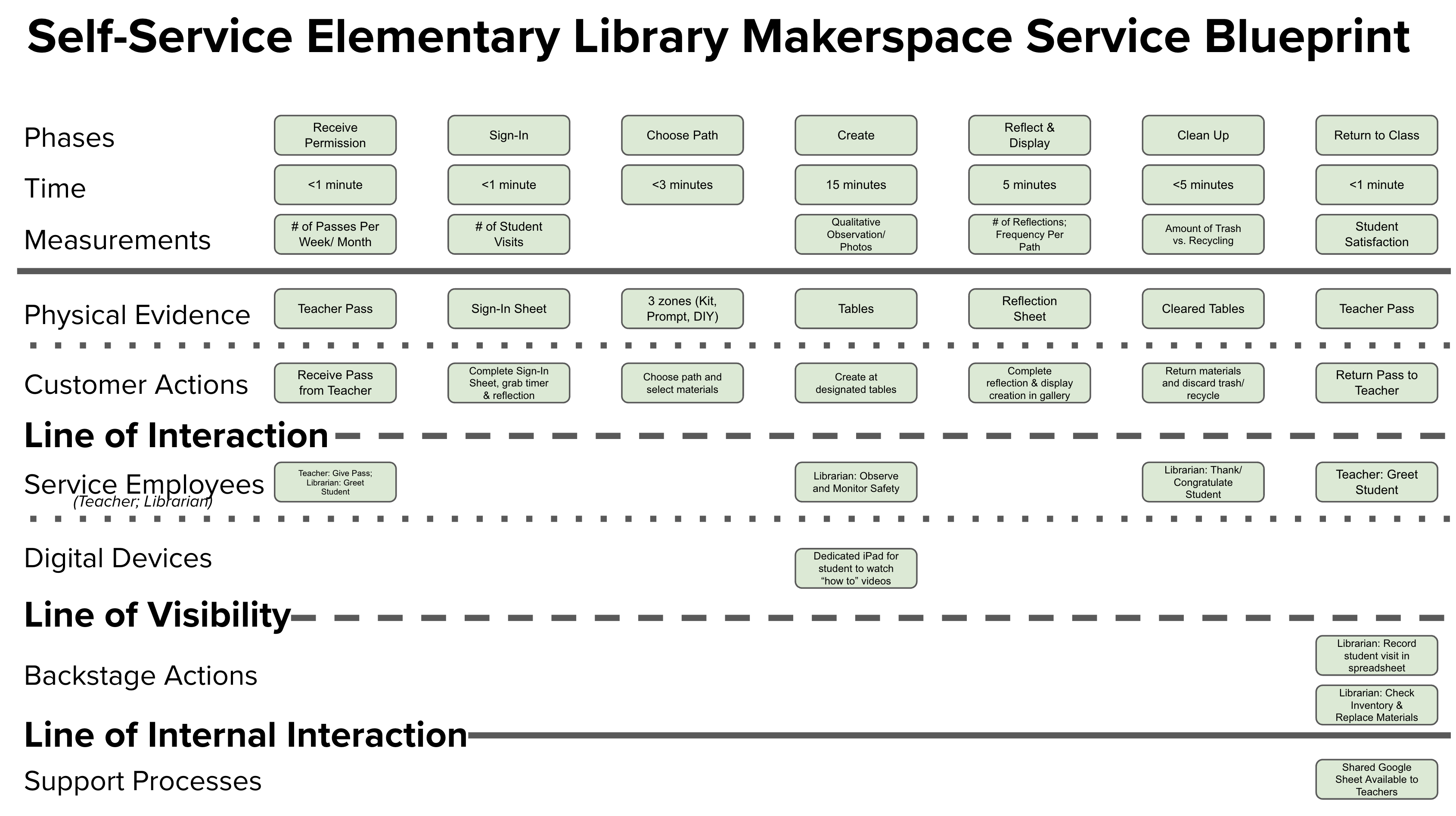

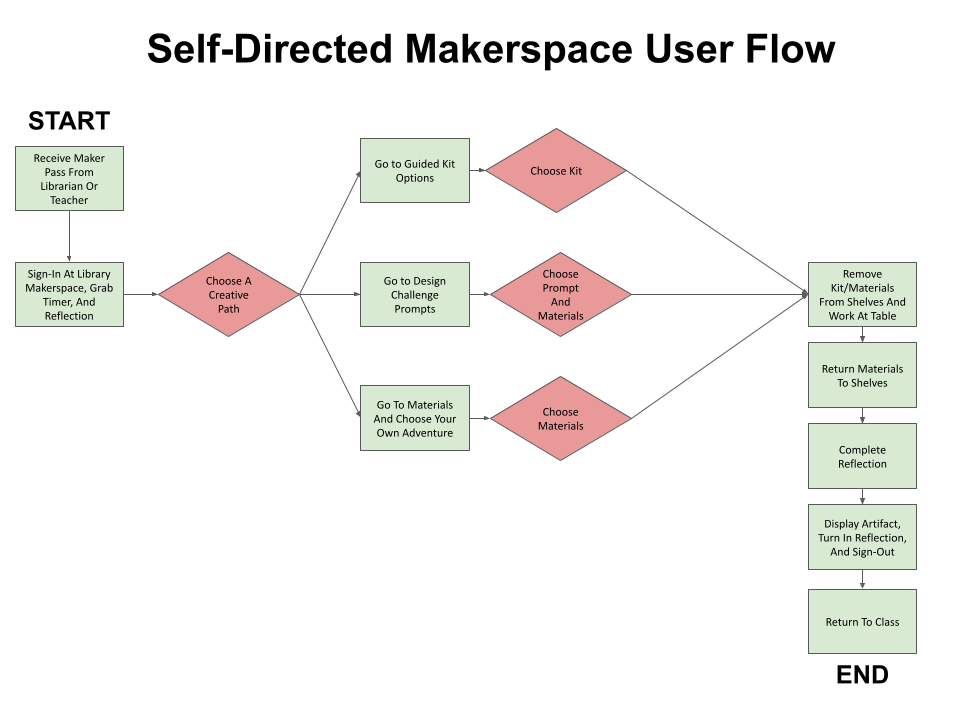

Lastly, we discussed how they anticipated a student could enter and move through the space. The librarian came up with the idea that teachers could award students with a “Maker Pass”, which they could use for 30 minutes during free time (e.g., recess) or when they’d completed their class work early. We concluded that we could focus students’ efforts into two categories to allow them the choice between learning something new through a kit or completing a design challenge prompt using available craft materials. To create this student user flow we transformed the unused corner of the library by using old shelves to create stations: 1) sign-in/out, 2) kit options, and 3) challenge prompts and craft materials. We consulted with other librarians and makerspace facilitators (i.e., subject matter experts) via phone and email to gain feedback on our proposed solution.

As we refined and aligned on these ideas, we collaboratively mapped out a service blueprint to visualize the relationship between the self-directed makerspace components, including people, props, and processes with frontstage and backstage actions (see Figure 4).

Experimentation

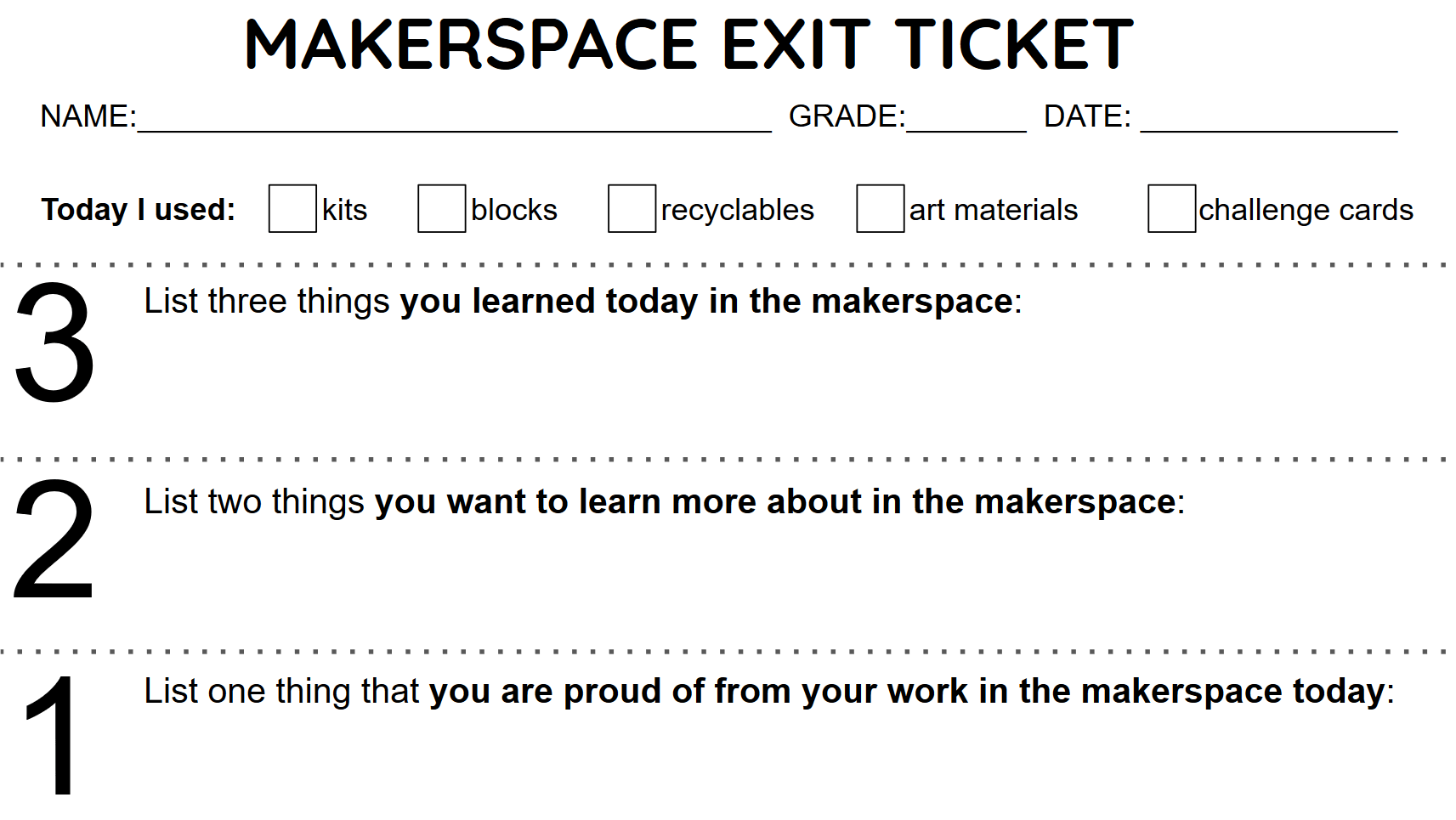

The experimentation step involved the development of design challenge prompts that the elementary students could use with the available craft materials without adult supervision. The librarian found some resources online while I had existing challenges to draw upon. Additionally, I chose to involve my university students (i.e. teacher education majors) to collaboratively generate new ideas. I hosted a one-hour brainstorming session where my university students and I examined existing design challenge prompt resource structures available online and discussed options for developing open-ended challenge prompts that targeted various content areas and approaches for assessment. I facilitated the session with sticky notes and whiteboard strategies to synthesize the group’s ideas (e.g., affinity mapping, dot voting), which were then assigned as tasks for my university students to develop into sets of challenge prompts and a makerspace reflection worksheet to serve as a formative assessment and accountability mechanism (see Figure 5 and 6). The completed prompts and reflection were shared with the librarian as a digital resource, which they printed and made available at the elementary makerspace.

During the session, my university students also collaboratively wondered how they could develop engaging instructions for elementary students with varying reading abilities. After a quick scan of Pinterest (a.k.a., Every teacher’s go-to source of inspiration on a budget), my university students grabbed recyclable materials in our classroom and started making a portable inspiration board to provide friendly instructions and recyclable inspiration for the elementary students (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Examples of recyclable materials and suggestions for simple building ideas

Lastly, the new self-directed makerspace service was tested with a small group of elementary students at the library. This involved the librarian selecting 6 students to come in and use the space for 30 minutes without adult interaction. I observed the ways that the students interacted with each station throughout the process, taking note of successes, struggles, and frustrations along the way (see Figure 8). Afterward, the librarian and I had a brief focus group with the elementary students to discuss their reactions, thinking, and suggestions. While all of the students were able to use the kits, task prompts, and craft materials on their own without adult supervision, 3/6 were confused about the sign-in/out procedures because they were in the same location. Additionally, all 6 students agreed that the original reflection sheet seemed like “boring work” and was too long for the students to complete within the time limit (average time to complete was 9 minutes).

Evolution

For the evolution of the space, we modified the procedures to bring the experience a more natural start to finish flow by providing a separate basket to turn in used timers and completed reflections at the far right of the space. Secondly, we created a shorter “exit ticket” style reflection sheet that was quicker for students to complete (average time to complete was 2 minutes, which was a 78% reduction). Additionally, this new exit ticket format was easier for a library volunteer to scan at the end of each day to send digital copies to the students’ teachers for accountability (see Figure 9). The original reflection sheet was still available for teachers who wished to assign an extra writing-intensive reflection to their students outside of the designated time in the makerspace.

Lastly, a final user flow was created to illustrate an overview of the improved user journey (see Figure 10).

Impact

After implementing the new service design, the library saw a 68% reduction in safety incidents, dropping from 25 to just 8 minor incidents over a semester. This new, lower rate of incidents aligned with the safety record of the library before the original makerspace was introduced.

Additionally, the average time to complete the reflective exit ticket decreased by 78%, from 9 minutes to just 2 minutes. This change gave students more time for creative work while still completing the required documentation for their classroom teachers.

Together, these metrics demonstrated that the new self-service elementary library makerspace was both safe and highly effective at increasing student engagement in classroom-related learning.